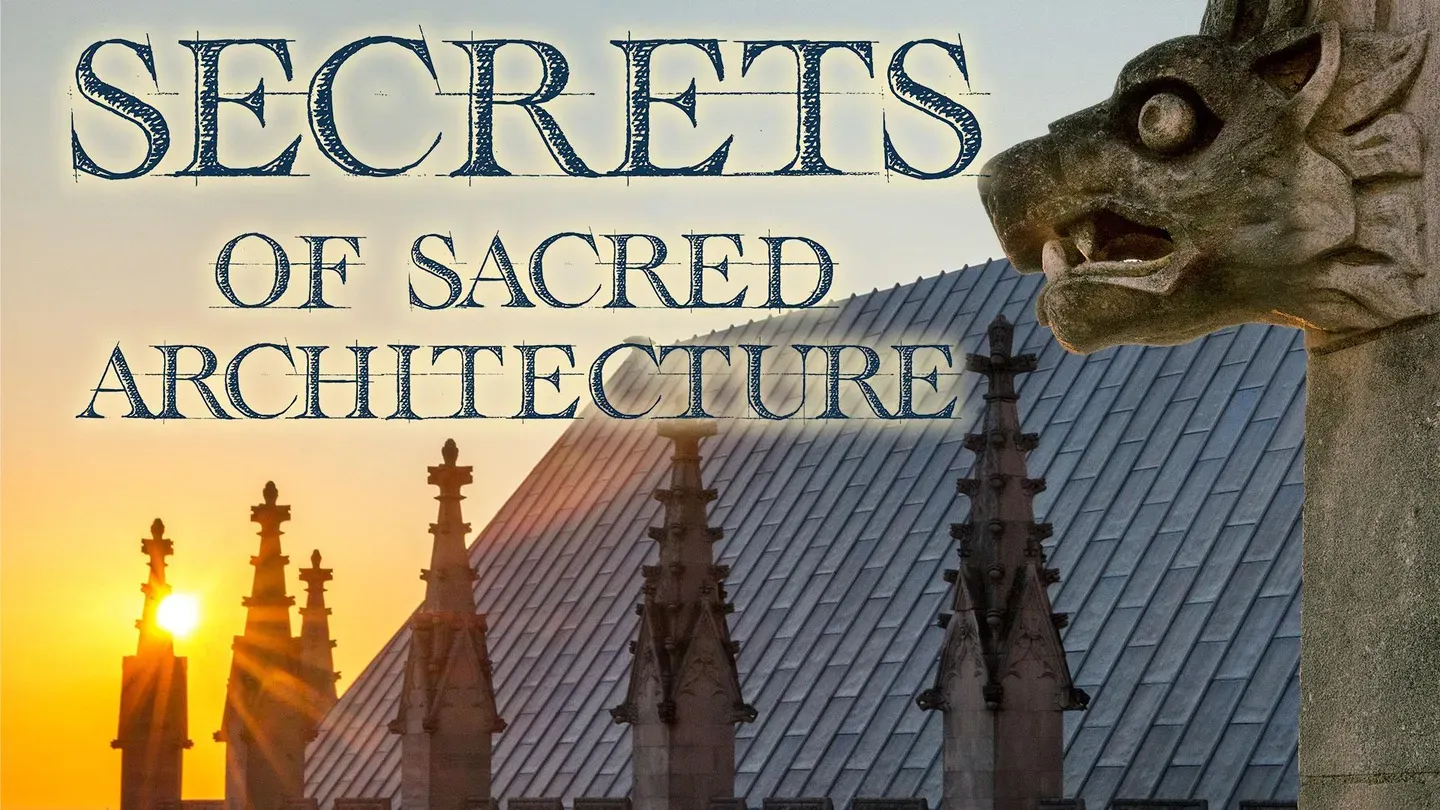

Secrets of Sacred Architecture

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Unlock the elements of design and unveil the meaning in religious architecture.

For most of America’s history, sacred buildings represented our greatest feats of innovative engineering and artistic design. For a time, America’s tallest structure and its largest-capacity building were churches, and a Maryland church organ was the most complex machine. Unlock the elements of design that make these structures so fascinating and unveil the meaning in religious architecture.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Secrets of Sacred Architecture is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Secrets of Sacred Architecture

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

For most of America’s history, sacred buildings represented our greatest feats of innovative engineering and artistic design. For a time, America’s tallest structure and its largest-capacity building were churches, and a Maryland church organ was the most complex machine. Unlock the elements of design that make these structures so fascinating and unveil the meaning in religious architecture.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Secrets of Sacred Architecture

Secrets of Sacred Architecture is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(church bells ringing) - [Narrator] From the beginning, humans have looked at the natural world and wondered where did this come from?

Why are we here?

And how can we solve the great mysteries?

Find the hidden secrets?

And as we began to build, those ideas were embedded in our structures, from the Stone Age to the Modern Age.

The churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples we see today were built with a secret code of sorts.

Unlocking that code can tell us a great deal about our quest for things above and our passions here on earth.

(soft orchestral music) - [Announcer] Major funding for "Secrets of Sacred Architecture" was provided by Daniel Donn and Lori Ann Oberstadt, Rose DeMarco Keesee, and by Church Mutual Insurance.

(train horn) - [Narrator] In the 19th century, the people who owned the railroads became fabulously rich.

One of those moguls was William Banning of St. Paul, Minnesota.

He served in the state legislature and accumulated enormous wealth.

In 1914, the Banning family funded one of the most spectacular stained glass windows in the country, but there is a hidden secret in this window that's been lost to history until it was recently rediscovered.

One of the Bible figures looked exactly like William Banning.

- Well, there's a man looking down, and it looks exactly like the picture in the Minnesota Historical Society.

- [Narrator] The image is so high up, it can't be clearly seen with the naked eye, but once the first likeness was rediscovered in 2013, several more were soon identified, including Banning's wife Mary, their son William, and a mysterious still unidentified bearded man.

It was not uncommon in the 19th century to depict major church donors in stained glass windows.

It was an arrangement that brought building funds to churches and a lasting legacy to donors.

- So they might not be able to see it, but they might know exactly where it is.

And then they've been part of that group that's put their stamp on that building that's present in that building forever.

- [Narrator] Most of these secret images have been forgotten for more than a century, but they remain tucked away in stained glass all over the country.

Like so many architectural features, they're just waiting to be rediscovered.

(sirens wailing) The burning of Notre Dame was a stark reminder of the irreplaceable value of the great medieval churches, all built in a unique style we now call Gothic.

- You know, it's stone.

It's not going anywhere.

It's carved stone to give that feeling of permanence.

- [Narrator] The hallmark feature of Gothic design is the pointed arch, a structural innovation that allowed churches to soar higher and higher with larger and larger windows filled with colored glass.

- You walk in and the ceilings soar, and you just feel like you can fly.

- And then when you fill it up with smoke from the incense burning devices and it becomes this fantastic late afternoon light, and they're chanting in front of you in Latin, it's this mysterious language that's going on and they're dressed in these beautiful vestments and there's lots of gold and there's lots of color.

And oh my goodness, you are in another world.

- [Narrator] Gothic design reached its apex with Chartres Cathedral, built in France more than 800 years ago.

In an era when a tall building might be three stories high, Chartres towered 35 stories into the sky.

- Discovery of the power of the pointed arch and then the buttressing system, I mean, it was really quite phenomenal what those engineers produced.

- Gothic is one of those times when architects stepped out of the known way of making things into a new territory.

- [Narrator] But then Gothic architecture fell out of favor, abandoned by builders for centuries.

It wasn't until the 1800s that Gothic design was rediscovered, and then quickly became the single most popular template for new church buildings in America.

Why the revival?

Part of the reason is this.

(suspenseful music) Mary Shelley's book, "Frankenstein," was part of a larger movement to reconnect with the mystery of the Middle Ages.

- It's all about emotion.

It's all about, you know, fear, love, hate, right?

And Mary Shelley is part of that.

- [Narrator] As authors, musicians and artists rediscovered discovered the Gothic period, architects followed suit, creating new churches that evoked the awe and mystery of the Medieval Age, a style that came to be called Gothic Revival.

- The time you reached the 19th century, certain people are looking back at Gothic and saying, oh, this actually was a style that had important meaning.

- [Narrator] Anyone who steps into a Gothic Revival church today can immediately sense that the intent is to transport churchgoers to an earlier time and place, an idealized era when it seemed that all great architecture was church architecture.

- When people thought about Gothic architecture, you thought about it with a sacred space.

And so people were willing to bring it back.

- [Narrator] The soaring heights, massive stone, and especially the dancing colored light make an emotional connection.

- And so the quality of the space changes based on the interaction of color in the glass, with color that's coming just from the sky at a particular time of day.

The natural light in a church building reminds us that we are beings that exist on a journey that's spiritual, but we exist in an environment that is temporal and changing and moving in time.

- [Narrator] In recent years, scientists have rediscovered secrets about natural light that Gothic builders knew intuitively a thousand years ago, namely that daylight has profound effects on the human psyche, boosting attentiveness and creating a sense of well-being.

- Studies now have shown when there is daylight, as opposed to artificial light, test scores are better.

We learn better in natural light.

There's a reason that retailers like Walmart have put skylights in all of their buildings.

An expensive endeavor, but what they found out is people feel better when they're connected to the natural environment as opposed to completely dependent on artificial light.

- [Narrator] Among the best known of America's Gothic Revival churches is the Washington National Cathedral.

- Great Gothic Revival building, built actually with Gothic techniques of no prefabrication and no steel in that thing.

- [Narrator] The idea of a national church in the US Capitol dates back to George Washington, but the first stones were not laid until 1907, and the building wasn't completed until 1990.

The process took so long that some decisions made early on were not the same choices Americans would make today.

- We are a country supposedly founded on plural religious expression.

Why would you think that it would ever be appropriate in that context to have one church that represents everybody, especially because it's a church and not everybody worships in a church.

- [Narrator] Despite it's Protestant pedigree, the Washington National Cathedral welcomes people of all faiths and even connects visitors to secular icons as seen in the church's most curious artifact, a gargoyle styled to look like Darth Vader.

- You know, they promote that like crazy.

And then of course, there's a stained glass window in there to the Apollo moon missions with a piece of moon rock in it.

- [Narrator] The National Cathedral's massive grandeur is one way Americans express their faith through Gothic architecture.

At the other end of the spectrum are small wooden churches that populate much of the snowy northern tier of states, many built in a style called Carpenter Gothic.

- [Reed] They couldn't be simpler.

Just a little box with a pitch roof on top and some two by fours on the outside.

Nothing complicated about it, but beautiful.

- [Narrator] These simple churches may not get the attention of grand cathedrals, but they reflect the modest lifestyles of rural America.

- Churches tended to use what they had readily available.

I'm always amazed, however, at what churches were able to do with timber.

The community builds it, right?

They are functional and they are gorgeous.

They're simple rectangular solids.

They're basically a version of the same building type that a cathedral is, just made out of wood and smaller.

- [Narrator] Even small churches retain little hints of a bigger history, like the Gothic pointed arch shape that connects these buildings to a tradition dating back millennia.

The medieval Gothic period wasn't the only inspiration for American architects.

Some look back even further, getting inspiration from ancient Rome.

In the late 1800s, dark storms of social unrest were increasing.

(thunder clapping) Churches felt threatened by growing atheism.

The response was an architectural style called Romanesque.

These were churches that were hunkering down and readying for a fight.

The design was fortress-like, with rough stone and turret-style towers.

The windows were small rounded arches characteristic of battle-hardened ancient Rome, not the delicate soaring glass of the latter Medieval period.

- And they were understood as a vigorous, masculine type of activity.

These types of buildings were making the statement that Christianity is here and it's massive and it's going to stay here for a long time.

- [Narrator] At the same time, other churches wanted to project a very different message, a connection to the logic, reason and democracy of the ancient Greeks.

Churches built in this style, called Greek Revival, looked like they'd be at home in ancient Athens, and make a statement about the congregation's connection to certain timeless boundaries.

- There's a formality to those kinds of architectures to Greek architecture that translates nicely to church.

And so to have these solid regular architectures that we know, we know they're historical, we know that they tie to something before us.

- [Narrator] Christians were not the only groups building places of worship that echoed an earlier time.

This building, for example, might appear Arabian, but it's actually a Jewish synagogue in Cincinnati, built the mid-1800s.

The design reflects a look from 400 years earlier in Islamic Spain during a rare period when Jews were free to practice their religion.

The style, called Moorish Revival, was a popular choice for American synagogues.

- And so you had Jews and Christians living with Muslim leaders all in the same place, and they all got along.

And so there are a surprising number of synagogues that are built in the 19th century that reflect this Moorsh period.

- [Narrator] In the early 20th century, interest in reviving old forms of architecture began to wane.

There was a desire to start fresh, a movement that came to be called Modernism.

- The Modernists are freed by the use of materials and by the tremendous roiling change in culture, in general, to look all around them and ask the question, why does something have to be the way it is just because it was that before?

- [Narrator] This new generation of architects stripped away everything that came before, rejecting thousands of years of traditional design.

For many church goers, the result was shocking.

- So the minimization of decoration and ornament and these forms that were rectilinear and simple, and they were hard for some people to wrap their heads around, that's for sure.

- [Narrator] One famous example is the Air Force Academy Chapel in Colorado.

Designed by architect Walter Netsch, it hints at older styles with elements like colored glass, but it's also distinctly modern.

- This is Walter Netsch, a very, very smart and challenging architect, trying to create multiple readings, multiple possible readings on behalf of the people using it.

- People can draw different things from art or architecture.

It does look like fighter jets shooting up into the air.

However, in my conversation with Walter Netsch directly, he did tell me that he designed it pointing straight up towards the heavens.

- Is it beautiful?

Oh my goodness, yes.

Is it a snowflake in the Rocky Mountains?

Is it a piece of the Rocky Mountains?

A chunk of ice that broke off and settled down on the hill?

It's all of those things, and it's more.

- [Narrator] Unlike most sacred spaces, this building needed to serve a range of faiths present at the academy.

Netsch's solution, to build separate spaces for each religion, remains controversial.

- The big beautiful part on top is for Protestants.

And then there's a floor.

And then there's two more big worship spaces, a fairly large one for Catholics and a relatively small one for Jews, right?

They're actually under the floor of the Protestants.

So you can imagine that some of those faiths look at that and interpret it as, huh.

Okay then.

This must be a Protestant country.

Is that what you're trying to tell us, right?

- [Narrator] The best known practitioner of boundary pushing modernism in church architecture was Frank Lloyd Wright.

- Frank Lloyd Wright, looking at the world and saying, if I'm going to build a church, it's going to look American.

I'm going to build it out of materials that are American, I'm going to build it with an expression that is rooted in this place.

- [Narrator] An example of Wright's unique perspective is visible here at Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, which Wright imagined as a dome on top of a bowl, the bowl representing God's hands holding the congregation.

The church can seat 800, yet the circular design means no church goer is more than 60 feet from the altar, reflecting an American view of egalitarianism.

- He completely wants the user to rethink how they engage with buildings.

- [Narrator] In a remarkable innovation, the dome is not even attached to the rest of the building, and instead floats on a channel of ball-bearings to allow for expansion and contraction throughout the seasons.

With a strong enough push, the entire roof could spin like a top.

- This man was radical.

Quite radical.

As an architect and as a person, the way he led his life.

People never quite came to terms with it.

- [Narrator] Wright's design for Annunciation was inspired by the 6th century Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, but Wright never copied older forms.

Instead, he used them as a launching pad to create something entirely new.

- He was doing something new.

He wanted architecture of an American spirit.

He didn't want these historical trappings.

- [Narrator] As with many of Wright's boundary pushing ideas, the innovative poured concrete dome was a challenge to maintain.

Interior insulation began to peel away, raining asbestos onto the pews, and tiles on the roof began to pop off by the thousands.

Wright always considered these kinds of issues with his buildings as irrelevant, because he was creating timeless works of art.

- When you know Wright, you know Wright always kind of thought he knew everything he was doing, right?

- [Narrator] Despite his reputation for ego, church leaders at Annunciation found Wright to be friendly and accommodating to their requests during the design phase.

And that positive relationship never soured, because Wright passed away in 1959, before construction even began.

The passing of Frank Lloyd Wright coincided with the birth of a new era in American sacred design, as Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist populations in the United States grew to the point where significant building projects were feasible in the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

- And when they came, they brought their ideas of what faith meant to them.

- We know them, not American context and especially the United States, that there are barriers for immigrant communities to kind of make their way, so it takes longer.

- [Narrator] Mosques, especially, have faced resistance in many communities, resulting in designs that try not to draw attention.

It's only been in recent decades that Islamic architecture in America has become more bold in emphasizing traditional elements like minarets and domes.

- Islam, I have to say that they're burdened by Islamophobia in our cultural context in general.

- And as you get more established as a community, you can begin to express yourself.

And the Muslim community has begun to be able to express itself in this country.

- [Narrator] For marginalized groups, whether Muslim, Hindu or Christian, the local church building is often the only gathering place that's free from prejudice.

- Share his dreams around you.

- In the African-American community, that was a place where we could go to be our full selves.

That was a place where you have black leadership.

That was the building we built, and we could take credit for it.

We built the other buildings, but this is the one that we could say was ours.

- [Narrator] As people of color congregated in city centers, wealthier suburbanites have kindled an entirely new kind of religious architecture that emerged in the 1980s.

You're seeing an example of one of the most radical changes in church architecture ever.

The mega church.

All are echoing a template of trying to look unchurch-like.

- Some of that expression of architecture in its simplicity is sending a clear message that this church is different.

- [Narrator] The idea is to make everyone, especially newcomers, feel welcome.

The traditional elements that signify a church setting have been removed, so there is no stained glass, no ornate woodwork and no steeple.

- So the church has to reach out and work to explain why they are relevant and why people might want to come into their building.

- [Narrator] These facilities bear a striking resemblance to a shopping mall or office park, and that's intentional because the architecture of American business is familiar and comfortable.

These churches have plenty of parking, clear signage, a coffee shop.

- [Girl] Thank you!

- [Narrator] And plenty of space for gathering and recreation.

While it might seem unusual for a church to have athletic facilities, it's not completely unprecedented.

Congregations have long considered recreation and community gathering to be central to their purpose.

- Bowling alleys in the 1890s were really popular in Protestant churches.

Basketball of course, was invented by Protestants as a game to keep particularly young men and boys off the streets.

- [Narrator] Mega churches today extend this informality into the worship service itself, reflecting a theology that sees God as approachable, friendly.

It's a stark contrast to the Gothic design that emphasizes a God who is awe inspiring and all powerful.

Most believers would say God can be all those things, but architecture does have an influence on how people understand their god.

- If you take the same religious practice and you move it from out of different buildings, you're going to come up with a whole different type of experience.

So the space itself participates in the religious experience of people.

- [Narrator] Both mega churches and Gothic cathedrals make a clear statement to the members and the larger community, and that's nothing new.

The central purpose that unites all sacred architecture is that the goal is to communicate.

Every steeple, every stained glass window, every parking lot is sending a message to the membership and the larger community.

(bright music) David Johnson is about to communicate with thousands of people over many square miles, but he won't be using any modern technology.

To send this message, David will need to climb high into a church tower, advancing toward a perch few people ever experience.

The journey is not without certain dangers, but David has made this trek many times before.

- Your heart, all your muscles, wonderful exercise, getting a workout just getting up those 108 steps.

- [Narrator] Now high above the street, David Johnson will play music on church bells.

(church bells ringing) This musical device is called a carillon, a keyboard connected to dozens of bells to create music.

- But for all of its size, for all of that bulk, there's immense tenderness, immense potential tenderness in a carillon.

(bells ringing) The possibility to play delicately, the possibility to produce all sorts of suggestive intricate sounds.

- [Narrator] Bells have been a part of church architecture for centuries.

In times past, church services were the only weekly event that required everyone to show up at a specific time and place.

And the best way to get a community in sync was to ring a bell.

The higher the bell was mounted, the further the sound would travel.

In playing carillons around the country, David Johnson has seen his share of very high church towers, some he hopes never to see again.

- You get inside the piece of the building that is a tower and literally climb straight up a wall with what amount to steps in a ladder.

I'd call it terrifying.

- [Narrator] While bell towers can reach dizzying heights, many are topped with an architectural feature that reaches even higher: a steeple.

Why do so many churches have steeples?

Are they symbolically pointing the faithful to God above?

Partly, but there is also another purpose.

- The steeple and the tower of the church actually marks its presence in the midst of a community.

Back in the day when we didn't have maps or maps weren't readily available, you could identify the town by the presence of the steeple.

- If you're trying to make a statement and you're trying to put yourself onto a landscape within an urban environment or wherever it might be... you're going to go for height.

- [Narrator] For many decades, the tallest steeple in America was New York's St. Patrick's Cathedral, towering above anything else in the city in the era before skyscrapers.

- St. Patrick's, the spires are 330 feet high.

At the time that they're built, they're the tallest things other than the Washington Monument in the country.

That's tall.

- [Narrator] No city exemplifies the competitive quest for height more than Philadelphia in the mid-1800s, which was home to something of a steeple arms race, each congregation driving to outdo the other.

- They're saying we're here, we have the tallest steeple, we're in important congregation.

You newcomers should be a member of our church because of that.

- [Narrator] To win the steeple war in Philadelphia, Tenth Presbyterian Church hired the architect known as the king of tall steeples, John McArthur.

McArthur would later become famous for designing the tallest building in the country, City Hall in Philadelphia, which held the title until it was eclipsed by the Washington Monument.

McArthur's steeple masterpiece was built to tower 248 feet above the street.

In an era before modern steel, it was unclear how to best engineer a structure 25 stories high.

Building the steeple with stone would be too expensive, so McArthur settled on timber, even though wood had not been tested at such extreme heights.

(wind howling) In a 1912 windstorm, the steeple was destroyed.

Only the base exists today.

It was a fate that was all too common in the race for the tallest steeples in America, as engineering had not get caught up with ambition.

- It was a height war.

At some point it was not going to work anymore.

- So there are many stories of many churches in the earlier days where they're ggoing to uild the biggest spire of the all until they don't, and it comes tumbling down.

(thunder clapping) - [Narrator] In 1878, a single storm toppled over 50 church steeples along the eastern seaboard.

While steeples are largely a Christian design, domes of a much broader history, used for synagogues and mosques, as well.

All domes connect back to the Pantheon in Rome, built in 126 A.D.

It was a stupendous achievement, measuring 142 feet across, half of a football field.

No one would build a bigger dome for a thousand years.

The Pantheon was a religious building dedicated to the Roman gods.

When Christianity became popular, many Christian houses of worship continued the tradition of including domes.

Most famously, St. Peter's in Rome, home of the Catholic Church.

- It's really with the design of St. Peter's in Rome, back in the early 1500s, all of a sudden you're like, wait a minute.

Now the dome, the dome is the thing.

- [Narrator] In America, the United States Capitol building was modeled on St. Peter's, and stood as the largest dome in the country for decades.

But of course, the US Capitol is not a church.

St. Josaphat is a church, and its don't was touted as second only to the capitol in size.

St. Josaphat was the brainchild of a blacksmith turned priest named Wilhelm Grutza, who wanted Milwaukee, Wisconsin to have a replica of Rome's St Peter's.

- And then of course, for Catholics with St. Peter being the most important church in Catholicism, why wouldn't you try to recreate that if you could?

- [Narrator] But how could Grutza make it affordable enough to build?

The stonework, especially, would be prohibitively expensive.

Early in the process, Grutza came up with an ingenious cost-saving idea.

He bought the condemned post office in downtown Chicago for pennies on the dollar.

- Then they found out that a building was going down in Chicago and they got the stone on the cheap for that.

That's pretty good.

- [Narrator] Grutza had the building moved, piece by piece, more than 100 miles.

500 rail cars of stone were then meticulously rearranged like a box of Legos to build the church and dome.

The result was stunning, but the constant fundraising took a toll on Grutza.

In 1901, with construction finally completed, Grutza said the very first mass in the church of his dreams.

And then promptly died.

The church stands today as a monument to Grutza's vision and his congregations dedication.

More than 2000 people can sit under the dome to attend mass or enjoy a Christmas concert.

But was this really the largest church dome in America?

The people of Utah would disagree.

In 1867, Brigham Young had a problem.

As the leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, his church membership was booming, but they couldn't all fit under one roof.

Young's solution?

Build a bigger roof.

More specifically, he built a tabernacle with a dome large enough that 15,000 people could worship together.

At first, no one was quite sure how to build it.

- Brigham Young, the head of the church, had strong interest in architecture and engineering.

He had built bridges and lots of buildings, and he was fascinated with the structural systems.

- [Narrator] Young got inspiration for the tabernacle one morning at his breakfast.

He stared at a hard-boiled egg, then cut it lengthwise, intuitively sensing he had stumbled upon one of nature's strongest shapes.

Young wondered how big the egg idea could be scaled up.

His architect, Henry Grow, delivered the answer.

A 150-foot unsupported span.

- It's made with no nails because nails were expensive.

And so it's built with wooden dowels.

Those are wooden nails that you hammer into wood, and they expand when they're wet and they kind of fill the space, and held strapped together with leather.

And the leather tightens when it dries, so wet leather was put around these structures and contracted and held them together.

It's an engineering marvel.

It really is an engineering marvel.

- [Narrator] Perhaps the most amazing design feature is the building's acoustics.

Built for sermons in an era before electricity, the strength of a single person's voice would need to be audible to more than 10,000 people with no microphones, no speakers.

Young was proud of his booming voice, and Grow strategically positioned the pulpit so that reflected sound would carry.

Famously, a brass pin dropped in the front of the church could be heard 200 feet away.

- And the architecture's helping them.

The building, the shape of the roof, the ceiling there with the curve, is helping, and the curved seats there, is helping his voice project out to the audience.

- [Narrator] Never before in history had such a large crowd been able to hear a single speaker, but Brigham Young pulled it off thanks to bold engineering and a booming voice.

(playful music) Gargoyles are surprisingly common on American churches, but they are up so high, most people never notice the odd creatures that look like strange animals or demons.

- Gargoyles our way that masons have fun.

And many of them are funny looking.

They don't look serious.

- [Narrator] Why have these beasts been so common in church architecture?

Water is the enemy of church foundations, so builders looked for ways to throw water as far from the base of the structure as possible.

Gargoyles are positioned at the end of a water downspout and vomit water during a significant downpour.

- So this is your tip.

If you are ever by a cathedral with gargoyles in a huge rainstorm, get out of your house, go over there because it is just shooting out.

It was amazing.

- [Narrator] Gargoyles were such a popular element of church architecture that builders began adding these carvings in places without downspouts, calling them grotesques.

For the stone workers who labored for years on a project, gargoyles and grotesques were an opportunity to be creative.

- And each time we're going to do it, we're going to do it a little differently.

Because, you know, the guy that did it before me, he's a hack.

I'm going to do mine like this.

This, look at this.

This is like, if you thought that was a dragon, wait until you see this dragon.

Who needs dragons?

I'm going to do mine.

This is a guy spitting water right out of its mouth.

So over and over again, we reinterpret it.

- [Narrator] One theme of most gargoyle design is to represent hellish creatures who would never set foot inside a church.

Increasing the contrast between what was seen as the ugly corrupt world outside the building and the beauty and sanctuary inside.

- I think they're scaring you.

I think they're always scaring you, right?

To be faithful, to not be wrong, to not do wrong.

- [Narrator] In America, most stone carver's names have been lost to history, but not all.

In fact, the artist who carved this got his start carving gargoyles.

His name, Gutzon Borglum.

Long before Mount Rushmore, Borglum toiled in relative obscurity as a sculptor at St. John the Divine in New York City.

But it was his work on the church's angel sculptures that made national news by igniting a scandal.

That's because Borglum's angels were female.

Church leaders wanted only male angels, and wouldn't back down.

Borglum was so irate, he destroyed his work.

The tirade turned Gutzon Borglum into a celebrity.

Most stone carvers weren't quite so dramatic.

In fact, there is a centuries long tradition of making gargoyles that are designed to evoke a laugh.

- They're so interesting because that's the moment where artisans really get to do something fun.

- [Narrator] And that explains the Darth Vader gargoyle at the National Cathedral.

The church held a contest in 1986, and invited ideas for a new gargoyle on the north or dark side of the building.

It's no surprise that Darth Vader won.

Stained glass has been central to church design since the Gothic era, and even before.

It stood as the most extraordinary art available to common people in medieval times.

But the beauty of stained glass isn't visible from outside.

Instead, townspeople had to enter the church to experience the grandeur of color in light.

In the United States, stained glass was slow to catch on because early American Protestants saw the art form as frivolous, unnecessary.

- Those Puritan groups, they didn't want any of that manipulated light.

They wanted pure white light coming in through their windows.

- [Narrator] As other denominations of Protestants and Catholics immigrated to America, interest in stained glass was renewed.

One reason is that the images in these windows tell stories and reinforce teachings that bond the community.

Even today, new stained glass installations reflect the continuing story of the church, like these windows at Trinity in Chicago, a predominantly African American congregation.

- And you can stand there and study that glass and learn a lot about the African-American experience.

They are scenes.

You'll see Martin Luther King giving his "I Have a Dream" speech, Harriet Tubman bringing people through the Underground Railroad.

- [Narrator] Perhaps the most important stained glass storyteller in America was Louis Comfort Tiffany.

He was best known for his lamps, but that was just a sideline.

For most of his career, his focus was church windows.

Tiffany's workshop churned out thousands, most still in place all across America.

- You should recognize the fact that Tiffany was a very smart businessman.

- [Narrator] And as the business grew, Tiffany pushed hard for innovation.

He developed a technique for stretching and twisting glass.

He mastered the combination of different colors, creating textures that mimic nature.

- He studied chemistry and he really took the opportunity to experiment, and so he was looking for new techniques.

- [Narrator] Tiffany hired a team of designers to develop his windows.

Among the more noteworthy was Agnes Northrup, who created nearly all Tiffany's landscape motifs.

It was a major change in direction for American stained glass, moving beyond biblical scene to emphasize the spiritual dimension of the natural world.

- And so suggesting a kind of beautiful, peaceful scene.

And so in that regard, it's a different direction in glass, for sure.

- [Narrator] Northrup's landscapes added a sense of perspective and three dimensionality that pushed boundaries.

- So do have a sense in a landscape that is a stream that the stream really goes back into a further distant landscape and that there's hills in the back and that there's receding skies and that the trees get smaller as they get farther away.

- [Narrator] While Tiffany saw windows as a work of art unto themselves, other designers rejected this idea and imagined stained glass as a servant to the larger church design by transmitting patterns and colors of light that were more important than the image itself.

One ardent advocate for this view was an artist named Charles Connick.

- He said that the window shouldn't be a picture.

It should be part of the architecture.

- [Narrator] As a boy, Connick was bullied in school, so he stayed inside at recess to avoid the torment, and spent his time coloring.

- And then he also started to gain a little respect from his classmates because he would have all these wonderful drawings on the chalkboard when they came back from recess, and they would just, you know, marvel at how well he could draw.

So that was kind of his first earned self-respect.

- [Narrator] As a young man, Connick visited the cathedral Chartres in France, home to some of the most impressive stained glass of the Middle Ages.

There he had an epiphany, as he realized the real artistry of stained glass is the projection of fine tuned colors, combining like a musical score.

- How light penetrates the outside into the inside makes a difference in how the building comes alive to the people inside of it.

And so all through the day, the light changes and the quality of the space changes with the light.

- [Narrator] Connick's focus on color can be easily seen at one of his masterpieces, House of Hope, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Here, the light is always changing throughout the day and across the seasons, all carefully tuned to create an environment of beauty and wonder.

- When clouds move there's animation on our glass, and we are physical beings that need light in order to change our mood.

- [Narrator] The changing beauty and emotional impact of stained glass is the reason this art form endured as a fundamental element of church design.

The mosaic colors of Connick to the intricate landscapes of Tiffany, and the artistic contributions of dozens of other artisans all contribute to an art form that seen by more people every week than all the world's museum exhibits combined.

(soft piano music) Christian churches fall into three main categories: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox.

Once inside, all three types have a surprising number of similarities, despite looking wildly dissimilar.

In the front, most Christian churches have a prominent pulpit where sermons are delivered.

Over time, pulpits have been used less and less, as sermons are often delivered closer to the membership.

- The necessity of being elevated becomes less important than being able to move freely so that I can project side to side and move closer to people that I'm trying to engage in whatever message I'm presenting.

- We don't make up in our mind in 2014.

- [Narrator] For Protestants, this connection is especially clear in churches with a large African-American membership, where the preaching reflects a dialogue between pastor and congregation.

- It is a dialogue.

It's a conversation.

You know, the pastor or the preacher is saying what they're saying, and then the congregation is responding to that.

And it is in real time.

Though, because of that, you're not going to have a lot of distance between people Because he needs to see me go, right?

We're on the same page, you know?

So people are going to be closer together.

- [Narrator] Catholic churches are likely to include statues of biblical figures or later saints.

Orthodox churches have their own unique images and art, often called iconography.

Protestants run the full range, from the highly decorated to the extremely spartan, the latter reflecting a strain of American Protestantism that dates to the pilgrims and Puritans who first settled in New England.

Superficially, Jewish synagogues might seem similar to Christian churches.

It's common for a synagogue to have pews for seating and similar artistic expressions.

Both Jewish and Christian houses of worship have seating, but Muslim mosques do not.

Mosques do house a weekly gathering, which includes prayers and a sermon typically delivered from a raised platform.

(orchestra warming) This historic church is setting up for its biggest day of the year.

On the Christian calendar, Easter is the most important holiday, but it's Christmas that attracts the largest crowds.

And one key reason is music.

(bright orchestral music) Most American churches are designed with music in mind.

Some feature domes, which have acoustic properties to enhance the sound.

Typically, there is special seating for a choir.

Sometimes in the back of the church, but in the past century, many choirs have been moved to the front.

Next to the choir's location is typically the home of the most popular church instrument: the pipe organ.

(organ music) - We don't typically think of the pipe organ as technology, but in fact, that technology was brought in to enhance the worship.

- [Narrator] Prior to the Industrial Revolution, pipe organs were the most complicated mechanical devices built by humans.

Yet even modest churches in America are likely to have an organ.

How could they afford it?

Part of the reason is this.

Steel mills made Andrew Carnegie enormously rich.

A church-going Presbyterian, he used some of that money to fund church pipe organs, nearly 8,000 around the country.

♪ Come now fount of every blessing ♪ - [Narrator] Many churches have switched to more contemporary musical instruments.

♪ Streams of mercy never ceasing ♪ - [Narrator] The advent of modern music in church has created an architectural challenge.

Space needs to be reconfigured for drums, electronic equipment and featured singers.

- Praise band, very different experience and very different acoustic required for contemporary praise band experience in worship than for more traditional sacred music.

♪ In morning when I rise ♪ Give me Jesus - [Narrator] In many churches, the area in the front that formerly was reserved for specific activities has now morphed into a blank slate platform that can be adapted for a range of uses.

♪ Jesus - There's just a lot that you can do with lighting to evoke a certain kind of emotion.

So I think that if there's one element in the church that in our church architecture that you can use to create theater, it would be lighting.

- [Narrator] This creates something of a curious juxtaposition in architecture, with the inside of the church reflecting the latest in modern music, technology and graphics, while the outside often echoes traditions from a thousand years before.

But that should not be a surprise.

American religion has always bridged two worlds.

Every house of worship has dual roles: to engage the community as it exists today, and to maintain a connection to ancient truths.

It's not easy to pull off, but the quest is visible every day, reflected in sacred architecture across the country.

- This is the most important building for most everyone.

- You're entering into something that's unique and special if this building is different from anything else.

- In architecture, when it's well done, you are never far from someone delivering a message.

- What's important is that you're inspired, and that you are, you're seeing things that inspire you and remind you that you are a child of God.

- So every faith, no matter what it is, finds a way to take their beliefs and manifests them in built form.

And that's an incredibly powerful thing.

- [Narrator] While great architecture is beautiful, these buildings were not designed to be toured like museums.

Their purpose is to serve as a gathering place for people.

- The church, which isn't just the building, it's the people that occupy the building.

That's the church.

(soft music) (bright orchestral music) (air whooshing) - [Announcer] Major funding for "Secrets of Sacred Architecture" was provided by Daniel Donn and Lori Ann Oberstadt, Rose DeMarco Keesee, and by Church Mutual Insurance.

Support for PBS provided by:

Secrets of Sacred Architecture is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television