No Straight Lines

Season 24 Episode 6 | 1h 25m 44sVideo has Audio Description

Five queer comic book artists journey from the underground comix scene to the mainstream.

When Alison Bechdel received a coveted MacArthur Award for her best-selling graphic memoir Fun Home, it heralded the acceptance of LGBTQ+ comics in American culture. From DIY underground comix scene to mainstream acceptance, meet five smart and funny queer comics artists whose uncensored commentary left no topic untouched and explored art as a tool for social change.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

No Straight Lines

Season 24 Episode 6 | 1h 25m 44sVideo has Audio Description

When Alison Bechdel received a coveted MacArthur Award for her best-selling graphic memoir Fun Home, it heralded the acceptance of LGBTQ+ comics in American culture. From DIY underground comix scene to mainstream acceptance, meet five smart and funny queer comics artists whose uncensored commentary left no topic untouched and explored art as a tool for social change.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPart of These Collections

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[dramatic music] ♪ ♪ [light music] ♪ ♪ - When I was a teenager, that's when I first found Roberta Gregory and Mary Wings' comics.

And I remember reading those and just being transfixed.

- I was very tired of feeling hidden.

I was very tired of feeling misunderstood.

I needed to speak to other people.

- I started creating these Black characters.

And I was just super into drawing the Brown Bomber.

The Brown Bomber was not only African American, but he was a gay superhero.

- Defining ourselves was an exciting thing for me.

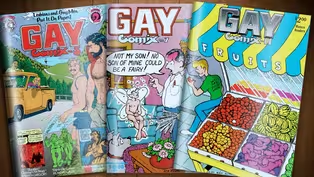

- Doing "Gay Comix" essentially was a turning point for me artistically.

The experience of being totally honest, suddenly it is a greater chance for high-voltage art.

- It's so out there about something that's so hidden.

I was just torn to doing it.

- I remember so clearly when I discovered "Gay Comix."

All of a sudden, here was this permission and a roadmap for exactly what I felt like I wanted to do in my life.

♪ ♪ [cat meows] ♪ ♪ - The idea of creating comics that aren't really about making people heroic is one of the things that I think queer comics have done the best.

[school bell rings] - I grew to hate being photographed as a teenager, specifically after puberty.

And it was because I didn't recognize myself in a photograph.

But when you're drawing yourself, you can draw yourself however you want.

And that's another reason why I think that comics is a medium that's so friendly to a queer author.

- You know, you're gay, you're lesbian, whatever you are, your identity, all of a sudden, you don't know how to be that.

There's nothing at all, no fairy tales even, no movies.

♪ ♪ - As a kid, I was always on the lookout for something that resonated with my perspective of the world, which was tough, beautiful, kickass women.

♪ ♪ And so in the comics, those were the kinds of female characters I was drawn to, especially the villains.

Like in Steve Canyon, the female villains were gorgeous and powerful and exotic.

[telephone rings] And then, of course, there was Hank in "Brenda Starr," who was very masculine appearing.

So I was finding dykes in comics from a very early age, I think.

♪ ♪ - When I was in my early 20s and had ambitions, I thought I would do a newspaper strip.

Comic books were considered slightly lowbrow compared to newspaper strips, because everyone saw newspaper strips.

And there were people that became famous and rich.

So that seemed like a worthy ambition.

Eventually, I learned that newspaper strips were highly censored.

[dramatic music] - [cackling] - In the '50s, there was a big scandal over the horror comics and crime comics, widely known as EC Comics.

Kids loved them.

Parents hated them.

Government people hated them.

There was a book about how horrible comics were for kids.

There started to be censorship in the air.

The Comics Code Authority was imposed.

And any comic that was displayed on a newsstand had to follow a certain set of rules.

You could never show law enforcement in a bad light.

There could be no mention of homosexuality, all sorts of things that were designed to reinforce the most bland vision of what American life should be like.

♪ ♪ [rock music] Then when you had the counterculture revolution, Underground Comix could never have passed the Comics Code Authority.

They were sold, in general, at head shops where they sold drug paraphernalia and psychedelic posters and things that hippies liked.

Anything you could think of could be in an underground comic.

[rapid gunfire] ♪ ♪ And they were full of stuff about drugs and uncensored sex, because Underground Comix were only sold to adults, theoretically.

[accordion music] ♪ ♪ - We felt very alone and isolated.

Most of our parents hated us or would have nothing to do with us.

And we were all living in secret.

And we started to read all the underground things that were coming out.

[rock music] I had seen R. Crumb comic books, which were really, really disturbing and an example of why feminists would want to make their own.

[accordion music] ♪ ♪ So, there was a Portland women's bookstore.

And I happened upon Trina Robbins' the Wimmen's Comix.

And I was so happy to see there in Wimmen's Comix was, "Sandy Comes Out."

♪ ♪ And then I was disappointed.

♪ ♪ It looked very superficial to me.

It's sort of as if one day she wakes up.

She takes a karate class.

She sleeps with a woman.

Men can't come into her house.

She's going to wear overalls forever and never shave her armpits.

Goodbye.

The end.

♪ ♪ And I thought, well, this has nothing to do with what it really feels like.

♪ ♪ And I didn't know what I was doing.

I grabbed a Rapidograph pen, and I sat on a sofa with bad lighting.

And I just sort of went at it.

♪ ♪ "Come Out Comix" is a very simple story about a woman who gets attracted to another woman, and oh, dear, what are they going to do about it?

And do they really feel that way?

♪ ♪ I really wanted to do something that showed all the emotion, all the sort of worry and trauma that you have about coming out, and all those things about really being a queer.

I did have two friends who had an offset press.

And they were two women who ran a karate studio.

So, we kind of printed it in the off hours.

I created "Come Out Comix" with absolutely no idea of distribution.

♪ ♪ I'm not even sure the word "marketing" had been invented.

I mean, it was sort of the boondocks, the nowhere.

It was-- the field was open.

It didn't exist.

And when I think more and more about why I did it, it was just a gift.

♪ ♪ I wanted women to have something that mirrored their experience, that felt good.

Because most of us just settle down into lives that are pretty repetitive.

And I wanted my lesbian sisters to go on an insane adventure while they're sitting in their armchairs and they have to go to work the next day.

♪ ♪ [dog barking] "Come Out Comix" came out of a period of great transformation.

Women were transforming themselves, breaking barriers right and left.

It was a very, very exciting time.

[dog barking] I had no idea that I was going to be part of such a big adventure.

♪ ♪ - I was in the room with Mary Wings, Trina Robbins, and Lee Mars.

And I definitely had a panic attack.

I remember us all sitting on the couch together and them telling us how they first got started in comics and how drastically different it was.

And it was just so overwhelming, because I was just so grateful that these people had come before and had helped me get to the point where I am today, where I can make comics about being a queer person and have people acknowledge them and take them seriously.

And without them, I don't think I would have been able to do that.

- I was born in San Francisco.

And just knowing, like, years later that there was an Underground Comix movement, but there was also like this critique initiated by women and queer folks, like, to create their own space.

To know that these are like the footsteps that we're walking in for this generation, that's something I don't want to ever forget.

♪ ♪ - When I was a kid, I got into so many different comic books.

I got into the "Fantastic Four."

I really, really loved them.

They were my favorite comic strip.

So I drew Batman.

I drew Spider-Man, Superman.

And I drew them well enough that I gained notoriety in the neighborhood.

"Oh, Rupert can draw the Hulk.

Have Rupert draw the Hulk."

[upbeat funky music] ♪ ♪ I grew up in Chicago.

And my hero in popular culture was Muhammad Ali.

- Cassius Clay of Chicago challenges Garry Jawish.

- Muhammad Ali didn't merely say he was the greatest.

He said, "I am so pretty."

- He's too ugly to be the world's champ.

The world's champ should be pretty like me.

- The degree to which white people hated his brashness increased my love for him.

One of the things that struck me was his confidence during a period of time where Black men were almost like not wanting to be seen, be literally the Invisible Man.

Once I started becoming really enamored of Muhammad Ali and his message, it was like a wake-up call.

I looked at these characters I was drawing.

And I thought, my God, why the hell am I drawing white superheroes?

And there was a certain degree of anger.

The word that keeps coming to mind, oddly enough, is "bamboozled."

I felt that I had accepted that the world of comics were white.

And that led me to create Superbad.

He had this giant 'fro that was designed to strike fear in the hearts of every white person.

His costume was the Black Liberation flag colors.

It was the very beginning of my comics for me being cathartic.

[light music] ♪ ♪ I decided I wanted to create a more whimsical superhero that was more original.

And I actually started discovering the history of another boxer, Joe Louis.

Joe Louis always struck me as more meek, more humble.

His nickname was the Brown Bomber.

And I started drawing these little sketches of this character.

He had these socks that went up to right below his knees and a cape.

I just became more and more humored by the whimsy.

[upbeat music] ♪ ♪ I was at Cornell College in Iowa.

And I was approached by the editor of the school newspaper saying that they wanted an editorial cartoonist.

So it was an incredibly pivotal part of my whole career.

♪ ♪ All of a sudden, the Brown Bomber became melded with this idea of editorial content.

And it was campus life.

So I did comics about the way men were treating women, kids who were pampered by their parents.

The Brown Bomber really had morphed into being a school mascot.

But he wasn't identified as a gay character, per se.

It happened my senior year, where I came up with the idea of these totally black panels, where the Brown Bomber is contemplating being in the dark and wanting to reveal who he truly was.

But he wasn't sure if he would be accepted.

[knock on door] I actually had people come to my dorm room and say, "Wow, I had no idea all along "you meant for the Brown Bomber to be gay, that he's gay."

And then there would be this light, they'd go, "Are you gay?"

And I'd have to say, "Well, yeah, I've been gay all along."

- Come on, Molly.

[gentle music] ♪ ♪ From the time I was eight or so and my father told me that some people earned a living doing this drawing that I was doing.

That got my interest because the adults that surrounded me in the little farm town, Springville, Alabama, none of their jobs looked terribly interesting.

And particularly the farmers.

Looked like that was an incredibly heavy labor job.

And that didn't appeal to me.

So I began wanting to be a cartoonist.

♪ ♪ The first time I was aware that any cartoonists anywhere were doing cartoons about gay people was in the "Advocate," the pre-Stonewall "Advocate."

It was called "Miss Thing."

And it was very campy.

Basically, he was someone that a straight person would never know about.

Like Tom of Finland, who is now well known.

And they have gallery shows in New York.

But for my generation, it was just porn.

It was just particularly excellent porn.

♪ ♪ It was a big step when I moved to New York.

I wasn't just interested in doing comics about gayness or even just in doing comics.

I wanted to do magazine illustrations and other things.

I didn't want to be pigeonholed.

[engine revving] [rock music] In 1969, by happenstance, I and some friends of mine happened to be witnesses to the Stonewall riots.

♪ ♪ [crowd booing] [crowd cheering] [horns honking] [door slamming] [glass shattering] ♪ ♪ Within the days immediately following the Stonewall riots, it became clear that a fuse had been lit.

♪ ♪ [cheers and applause] ♪ ♪ I became aware that there was a civil rights battle to be fought.

Then I felt like, you know, something has to be done so that every generation does not go through what I went through.

♪ ♪ And one of the ways that I felt I could contribute was to represent a world that had gay people in it.

- I have only just began to grasp the wealth of queer comics history, so to speak.

It's something that I feel.

You should always know your roots.

But these are very new roots for me.

- I remember Mary Wings said she thought she was the only lesbian.

To put yourself out there in a situation where you're going, "Am I a total anomaly?"

and to still put yourself out there, I mean, that's just amazing.

- If it hadn't been for people who came out before me in a time when it was much more dangerous to do so and been willing to make work, then my work wouldn't be received the way that it is now.

- I read "Dykes to Watch Out For" cover to cover at the Lucy Parsons Library in Boston, Massachusetts.

And that experience of finding that book and sitting in this library by myself and just really delving deep into these characters that this person had spent 25 years creating, that had a huge impact on me.

- I'm filling in the blacks on a very old comic strip.

It's very easy to fill in the blacks.

It's just a mouse click in Photoshop.

But for them to really look nice on their own, they should be inked in.

So I'm doing that after the fact.

I remember so clearly when I discovered gay comics.

The thought that I could draw about my own queer life was really revolutionary for me.

Let me think.

It was soon after seeing that first issue of gay comics, and being exposed to this wonderful world of these stories, that I forced myself to start drawing lesbians.

Because although I had drawn all my life, I almost exclusively drew men, which started to seem really odd to me once I came out and realized that I was, like, really interested in women.

Why was I just drawing men?

Donny, you're so funny today.

I just use Rapidograph ink.

But I put it in a bottle so I can get at it.

And I use a dip pen, a Hunt number 100.

But you can see it can be a very fine line or a very thick line.

It's very sharp and precise, but it's also-- it's got this emotionality to it, you know, in a way you can get so many different widths.

"Dykes to Watch Out For" evolved really slowly, first from these just silly drawings I was doing for my friends, just one image with a caption.

That was kind of like "The New Yorker" influence of my childhood.

I would always read the comics in "The New Yorker."

- [gasps] [dish clattering] [upbeat jazzy music] ♪ ♪ They were all just single-panel comics in the early days.

It was something that I published in the feminist newspaper where I worked in New York City.

♪ ♪ So this is kind of like my-- my final sketch that I'm going to draw from.

So I put my good paper down on top of it on a light box.

So this shines through.

And then I draw-- I redraw it all in pencil.

And then ink over it.

So the pencil is this beautiful evanescent stage that no longer exists, because I have erased it, and I've drawn over it.

But it's my favorite part of the process, is when the pencil is all finished and I haven't inked it yet.

- Why is that your favorite?

- Because it still has the possibility of perfection.

I haven't [bleep] anything up yet.

[delicate piano music] ♪ ♪ I didn't earn a living for a long time.

It took me until I was 30 to really have enough gigs that I could take that risk of quitting my day job.

My day job, at that point, was cutting and pasting.

It was before computers.

Really, like, wax and rubber cement, which was great training for being a cartoonist.

I loved it.

I love that challenge of having to fit a certain amount of text and a certain number of images into a given space.

♪ ♪ - If I can find what I'm looking for-- that's not the drawer.

That's not the drawer.

That's not the drawer.

That's what I'm looking for.

These are drawings that were either drawn while I was tripping on acid or that were inspired by the acid experience.

[light piano music] I was down in Alabama in Birmingham.

And I discovered Kitchen Sink Comics published by Denis Kitchen.

So I sent him some of my stuff I'd been doing for underground newspapers locally.

And Denis liked those and asked me to send more.

And so he began to regularly publish my stuff.

♪ ♪ In 1979, Denis, with whom I had this long relationship by then, he had published most of my underground comics, he said he was thinking about starting a new series called "Gay Comix."

So he said, would I be interested in editing it?

I realized it was really an ideal way to come out professionally.

♪ ♪ Denis.

- Howard, hey.

- You remember Molly.

- Of course.

Hey, Molly.

- Let's sit in here.

- Yeah?

- We can have some tea.

- All right.

Nice cup.

- You know, we were talking about "Gay Comix" a while back.

- Yeah.

- And I remember getting a letter from you about it.

But I don't know if you ever told me sort of what led you to think of it.

- I think-- was it a story you did in "Snarf," maybe, one of the comics, where Headrack came up.

- Yeah, that was "Barefootz" No.

2.

- Okay.

[funky music] ♪ ♪ - It just seemed to me the time was right.

I mean, I was doing-- you've got to remember, I'm doing other anthologies.

"Dope Comics," well, I was a card-carrying marijuana smoker.

That was easier for me.

I was doing "Bizarre Sex" comics.

- I was doing-- - Yeah, "Bizarre Sex Lives."

- "Wimmen's Comix" with Trina and others.

And it just seemed like, for me, what Underground Comix were partly about is for a forum for groups and individuals to speak their mind.

And it was kind of an offshoot of the Free Speech Movement.

And it's, like, it's time.

Comics were so suppressed for so long, my feeling was, let all the voices out.

And once I figured out-- it took me a while-- that you were gay.

And I just thought, well, jeez, you'd be the perfect guy to edit it.

♪ ♪ - That was scary.

You can't take it back.

The cat's out of the bag.

[bell dings] So I wrote to everybody who was in the world of Underground Comix.

I said, "I know that many of you may feel "that it's threatening to your career for you to be open about being gay."

As a gay person, I felt those feelings too.

But I feel like, you know, given the onslaught of anti-gay activity that it was really important that people be out.

And it's not just for political reasons.

People should be able to do art about their lives.

[typewriter tapping] We sent this letter to every cartoonist in Denis Kitchen's Rolodex.

- I know there were more than a handful of rather macho guys who were quite indignant that they'd gotten this form letter.

But I mean, like I said, who knows?

And there were a number of surprises that we never could have guessed, including some people who were bi and... - Mm-hmm.

[funky music] ♪ ♪ - I wanted to establish this is co-gender.

This is not a boys' club.

I said, I want this to be an honest comic book about the human experience of being gay.

I mean, even if you want to do a funny animal story, it needs to grow out of the real-life experiences of gay people in spirit.

I mean, it could be fanciful.

It could-- you could take all sorts of liberties with reality.

But what I didn't want was something that was all about camp or that was specifically just about sex.

I said in my little opening statement, I wanted this to be about people, not penises.

And some of the artists took me so literally that the issue was in danger of being so sex-free that I made-- my contribution to the first issue was the very sexually explicit story.

It was called-- "Billy Goes Out," was the name of the story.

It was about going out for a night of hopefully sex in Greenwich Village in the late '70s before the AIDS epidemic.

Externally, the guy was out looking for sex.

He was cruising.

It was about the inner life of the character.

Every panel had his thought processes above his actual actions.

And he had this thing called the rejection checklist.

[quirky music] ♪ ♪ But also talked about-- had things about his family relationships, all the things that might go through your head.

And the point was, people who entered that sexual world that was so freewheeling during the '70s, they were full-fledged human beings who had lives.

[upbeat funky music] ♪ ♪ - I remember in 1979 I had a friend who was always sick.

And nobody could figure out what it was.

And he would go to the doctor.

And they would give him some sort of diagnosis and give him some kind of medication.

And he never got better.

And then we started hearing about GRID, the Gay Related Immune Deficiency, and then AIDS.

- 800 cases nationwide, 300-plus of those fatal.

And every day, three more cases are identified.

And yet still, surprisingly few people are familiar with the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

[somber music] ♪ ♪ - And we lived through this period where it was this mystery.

And then it was this death sentence.

♪ ♪ AIDS was a huge part of our lives.

And our friends were getting sick and dying.

And we were helpless to stop it.

♪ ♪ And our whole community-- I don't know if I can talk about this.

♪ ♪ I can't talk about it.

♪ ♪ [crying] all: Fight AIDS!

Act up!

Fight back!

Fight AIDS!

Act up!

Fight back!

Fight AIDS!

Act up!

Fight back!

Fight AIDS!

Act up!

Fight back!

Fight AIDS!

Act up!

Fight back!

Fight AIDS!

- It was a frightening time.

It was a heartbreaking time.

I watched people behave in terrible ways.

And we wrote about it in comics.

It was hard to write about sometimes.

It was difficult.

♪ ♪ Some people told personal stories about characters with HIV and AIDS, like Howard did in "Wendel."

"7 Miles a Second" by David Wojnarowicz was really about the rage and the horror that was involved in this epidemic.

[water splashing] Some people did satirical comics about the reaction to HIV and AIDS.

[water splashing] - That's the kind of humor you would get from people with AIDS.

Humor is one of the ways that people deal with tragedy.

Death was in the air.

They weren't pretending it wasn't.

- Jerry Lopresti.

LHM.

Michael-- - Basically, you know, America at large was not interested in reacting.

Gay people stepped up to the plate.

- Michael McDowell.

- Joe Avella.

- William Maysle.

- Michael Babcock.

- Peter Neihaus.

- There's no other group of people I would rather go through a deadly epidemic with than the gay community.

- Howard Dill.

- Our response to the AIDS epidemic, as horrible as it was, made you proud to be gay.

- Alex Kovnor.

[seagulls squawking] [upbeat violin music] ♪ ♪ - Look at the highlights on that sausage sign.

The lettering is amazing.

You've got drop shadows.

You've got italics.

You've got outline.

Some have serifs, some don't.

It's classic, old-style, hand-painted sign lettering.

I love these two characters on the roof of the building.

But it always cracks me up that the little girl is carrying a mug that looks like a giant mug of beer.

And I think originally those were root beer stand signs.

But now, it looks like she's an exclusively drunken child, which I love.

I always drew comics.

In school, it was making fun of the teachers or the people in authority.

And art was a way for me to comment on what was going on.

And I am very opinionated.

And I have something to say about everything.

I didn't really think of being a cartoonist.

I just-- it was something that was accessible to me.

It was a pencil and a piece of paper.

And it didn't require a whole lot of expensive equipment.

[light violin music] ♪ ♪ I come from a mixed background.

I'm half Lebanese, half white-bread American mongrel.

And I didn't relate to the little girls in the books I was reading.

And I didn't relate to the downtrodden, struggling whatever.

I wanted characters like me to be victorious.

[dramatic music] ♪ ♪ [billiard balls clattering] I remember going to a gay bar when I was underage.

And that was amazing.

[laughs] Those are some stories.

I remember seeing all these older dykes and being fascinated by them.

And the drink was the-- what was that orange drink?

Tequila Sunrises.

All those pretty drinks, that bright colors.

And there were these big old dykes who had, like, been kicked out of the army.

And they were like buying drinks for their girls.

And I was watching everything and learning, oh, this is how you do it, right?

[indistinct chatter] And I remember hanging out, being just a little brat.

And that's really how I saw the queer world and learned about dyke behavior.

[upbeat music] [cat growls] ♪ ♪ My feeling was, I was creating sexual imagery for dykes.

And I felt like, well, why can't we have our own sexy comics?

[quirky music] ♪ ♪ Some women felt that my work was too sexist and I was objectifying women.

I'm a dyke.

I do objectify women.

I love them.

I find them sexy.

I love the fact that people were paying attention.

And if they got mad, then I was doing my job.

[upbeat quirky music] ♪ ♪ I never had an idea that this was a career.

This was what I did because I loved it, because it was fun.

In the early '80s, Howard Cruse had started the anthology comic, "Gay Comix," with an X.

And I sent something in.

And Howard said he would print it.

And Howard was just an amazing editor, an amazing mentor.

And as I went along in my career, every time I hit a wall of, oh, how do I do a contract, or how do I-- how much should I charge for this?

Or what if they don't pay me?

You know, call Howard because he'd know.

He'd done it, you know?

And so he really is the godfather of queer comics.

- My now husband, and for 37 years, partner, Eddie Sedarbaum, I met in 1979 after I had lived in New York for two years.

We met at a gay discussion group.

I quickly detected that he was a really interesting person to talk to.

And he had thoughtful things to say.

And it had possibilities of moving beyond just a hook up.

Here we are 37 years later.

- Have you ever remembered your coffee?

- Once.

I think I did once.

And starting with "Gay Comix" and then continuing through the '80s, I was drawing about the kind of people like Eddie and me and our friends.

In the third issue, I felt all the stories were about young, buff, gay men.

And I wanted to do something about older gays who were underrepresented.

So I created these two characters, Luke and Clark.

And the story was called "Dirty Old Lovers."

It spun off of some of the kind of times that Eddie and I would have.

Eddie and I have always been very uninhibited about, you know, saying lascivious things about what was going on around us or taking note of cute guys.

- Nice smile.

- And so the "Dirty Old Lovers," it was just about a stroll they took in their neighborhood.

And ultimately, they wound up at a bar.

And all of the other guys in this gay bar were being really snotty about these two older gay men.

This guy took umbrage at that and went home with them.

And so they had a nice, cuddly threesome.

[door hinge squeaks] It was an affirmative thing about getting older.

It was also just fun to write, because these guys are just so uninhibited.

And their repartee wrote itself.

- I have a-- I have a very early "Dykes to Watch Out For."

Oh my God, look it, yeah, it's crappy.

It's like just normal drawing paper with Wite-Out that's all chipping off.

And I can tell you I drew it with a Niji Stylus.

Isn't that weird that I can tell just by looking at the line what pen it was?

[accordion music] It was almost a mission of mine for a long time to show this stuff, just to show real bodies, people's real sex lives.

♪ ♪ I wanted to de-stigmatize lesbian sexuality and women's bodies.

It was something I felt really passionately about.

♪ ♪ Well, here's one after I introduced the characters.

And it's an episode where they're all on their way to the 1987 March on Washington.

[engines revving] ♪ ♪ About four years after I drew the first cartoon, I finally took the plunge into creating regular characters, like I had seen Howard do.

Never looked back.

Every two weeks, I had to further my characters' narrative.

And I had to weave in the latest horror that had happened on the political scene.

♪ ♪ Many of my characters were also consumed with all of this stuff that was going on, the Patriot Act, and all this sort of creeping fascism.

I kept track of this all with this crazy spreadsheet.

You keep track of the episodes across the top.

And down the side are all your characters.

So I would map out my stories almost like they were spontaneously generated.

Like, I put all this information into the spreadsheet, and I got a story out of it.

♪ ♪ - The first time I can remember seeing a trans guy represented in comics, I think, was probably in "Dykes to Watch Out For."

Oh look, I exist.

- You know, one way or another, we all have someone we're scared to tell something to.

And it's just a-- it's a great starting point for stories.

- [slurping] ♪ ♪ - I would religiously read Robb Kirby's "Curbside."

Wow, I really wanted to be a gay man in New York, because I'm still, deep in my heart, a huge fan girl.

[bottle pops] [people cheering] - I love that Jen Camper is an out Arab American hardcore feminist woman.

- The first queer comic that I saw-- that I was like, OK, this is gay, and like, I have to hide this from my family, was the "Wendel" comic.

♪ ♪ - Most of my comics are not about violence.

But this was a scene where Wendel and his friends are attacked by homophobes.

And you have a scene such as this where Wendel is getting hit in the face.

It's very central on the page.

For regular "Wendel" readers, it's shocking.

You know, we love Wendel.

We don't want him to get hit.

[seagull squawking] [delicate piano music] ♪ ♪ I decided, well, maybe I should have Wendel find himself in love with a guy and form a relationship.

♪ ♪ It was an area that had not been covered a lot, the actual development of a gay relationship.

♪ ♪ Wendel didn't have scars from being in the closet.

Ollie, you know, had a lot of leftover fears about consequences of being openly gay, had trouble coming out to his parents.

So that was drawing on the part of me that remembered that experience vividly.

There's a sequence when Ollie finally decides to come out to his family.

He's being very bold about it.

And he gets his little mass letter.

You know, and he puts it in the mailbox and then has an anxiety attack, you know, hugging the mailbox, and what have I done?

- Ten years or so after I wrote "Come Out Comix," there was a gay and lesbian comic scene.

It happened so fast.

And it grew so huge.

And I met amazing people.

And suddenly, I had a-- I had a whole wonderful group, national and international, around me.

It was very exciting.

[rock music] - I'm here at A Different Light bookstore for the opening of "Queer Cartoons!"

show.

And we have 51 artists in this show, 168 pages of fabulous cartoon art.

I put this show together with my good friend Dan Seitler, who's a wonderful cartoonist.

And we wanted to celebrate cartoonists and the gay artists that we know and promote-- We got to do pretty much whatever we wanted.

And that was really exciting.

I'm Jennifer Camper.

And I'm hanging out here in the bathtub.

[toilet flushes] [laughter] None of us made money.

But we had a whole lot of creative freedom.

- I'm Alison Bechdel.

And I draw "Dykes to Watch Out For" cartoons.

Another thing that was terribly exciting to me about comics was, no one was judging it.

No one was-- it was like this free play zone.

[upbeat piano music] There were absolutely no rules or limits.

People were drawing all kinds of naked bodies and sexual activities.

And the crazier something could be, the better.

- [belches] ♪ ♪ - I didn't feel like there was competition, because nobody was doing the same thing.

Each of us had a really distinctive drawing style and voice.

And we all were talking about different aspects of queer community.

♪ ♪ [engine revving] ♪ ♪ In the '90s, every major city had a gay newspaper.

We were all doing comics maybe for one or two newspapers.

And then suddenly, it was like, whoa, there's 50 newspapers in the United States that we could send our comics to.

[upbeat music] People got the idea that we can syndicate our comics.

♪ ♪ - "Windy City Times" in Chicago, I think they offered $25 for each strip.

And I think I thought, oh, OK, that would really help.

And then you get somewhat syndicated to a couple of other papers, and then they pay you.

Then it starts being significant.

[knock at door] I went from having the strip published in college, that community, and then in Portland.

And then when I went to the Bay Area, it was published in a queer newspaper, "Bay Times," and then in "The Sentinel."

♪ ♪ When I left "The Sentinel," the biggest step for me with my comic strip is when it first started being published in "SF Weekly."

♪ ♪ It was like a larger playground.

I realized that I had a unique voice in those publications to challenge.

I experienced a lot in the gay community as an African American.

So I'm like-- I'm using this as an opportunity to talk about these things that we should be addressing.

[bell dings] [accordion music] - From the very first time I saw an image of the Brown Bomber and Diva of the World, I was just like who is that?

Who are these characters?

I love them.

Upon reading more of his work, I was just struck by the level of analysis and the intersectionality that he was able to portray in his work, talking about the experience of being Black and gay or being Black and woman.

- To be Black and queer and only know about Rupert's work, Rupert Kinnard's work two years ago, at Queers & Comics, is kind of-- it was profound to me.

But also it made me very sad.

Because I'm like, how many other Ruperts are there that I don't know about that I could have used?

Not only was he making queer comics about being Black and queer, but this was way, way back.

And it's not a new thing.

And it would have been nice to not have to struggle, is it OK for me to do this?

♪ ♪ [crowd cheering] - The differences between Rupert's work and my work kind of reflect the times that we were working in.

You know, Rupert's characters were very much directly interfacing with white characters that didn't get it.

And here and now, as artists, we don't necessarily have to put a white character at the center of the narrative anymore.

- I'm privileged that I have access to so many people who happen to look like me.

♪ ♪ - Everybody takes inspiration from the generation before.

After Art Spiegelman came out with "Maus," there began to be serious literary graphic novels.

There was always the question that, could I do a graphic novel?

And I thought, there's been very little coverage about what gay life before Stonewall in the South was like.

[light music] ♪ ♪ And it was all of this ferment in Birmingham about civil rights at the same time.

So I would be able to cover some ground that hadn't been covered in other gay literature.

Going into a project as long as "Stuck Rubber Baby," it was a big, scary step.

I got a contract.

And I had an advance covering two years.

♪ ♪ But I realized that to tell this story, you needed to feel the world around the characters.

It couldn't be done without putting time into drawing in more detail, with more shading than I had ever done before.

♪ ♪ I began to panic when I saw that I couldn't go nearly as fast as I had thought.

And then I was thinking, oh, no, this is going to be a disaster.

How would I-- how would I pay the rent?

And finally, I just had to change my attitude, and I said, well, I'll just have to take whatever time it takes.

And it wound up taking four years.

A lot of people are surprised that these are as large as they are.

These are actually 2 1/2 times the size that they appear in the book.

It allows me to put in detail the large amount of cross-hatching to try to create a shading, a graduated shading from lighter to darker.

The book uses a lot of that.

This is an example of comic book conventions.

So things like, in this case, the dog, which intrudes into the surrounding panels.

The feeling of threat is right at the center of the page.

If possible, I like to always have what I call an anchor panel, the panel I most want the eye to fall on when the person turns the page.

And in this one, it would be this.

But they still need to read the panels that go before to see how it fits into the story.

But it gives coherence, you know, if you-- so it's not just a bunch of random rectangles.

In each given layout for the page, I tried to suggest the atmosphere that's going on in the scene.

Here you have, I wanted a certain feeling of chaos, because they're in the middle of a riot.

[dog barking] [brakes screech] [whistle tweets] [crowd chanting indistinctly] It was a wonderful artistic experience, as financially disastrous as it was.

♪ ♪ - For a long time, I kept getting more gay newspapers every year.

It was like this growing thing.

I was selling more of my books.

I was publishing these collections of the comic strip.

And then all of a sudden, in the late '90s, turn of the millennium, everything started drying up.

There was the internet, but there was also the rise of Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble, these-- you know, these chain bookstores that were changing the whole publishing landscape, you know.

Anything fringe or alternative or independent was dying.

- "Gay Comix" stopped publishing.

A lot of us were doing great work.

But we weren't really finding places to publish it.

That pissed me off.

So I decided to do an anthology called "Juicy Mother."

And the cover is by Karen Platt.

And it's a big gay party.

Each "Juicy Mother" had a cartoon jam.

And a cartoon jam works where one person does a panel...

Gives it to the next person, and they do a panel, and they give it to the next person.

And it goes around a few times.

And you get a whole story.

What's fun about a cartoon jam is, you get to draw each other's comics.

But what's weird about it is, you don't have control.

And suddenly, you've got to give up your character.

And somebody else could kill them off.

So I did a lot of cartoon jams where I kind of edited them and brought people together.

And back in the day, it was all done by mail.

And they're great.

They're crazy.

They're nuts.

And they're a lot of fun.

[upbeat punk music] ♪ ♪ - As the gay ghetto was crumbling in a way, there was also the rise of the punk and DIY movement.

And so people started making their own zines.

♪ ♪ Maybe you couldn't get published by a major publishing house or even a minor publishing house, but you could make your own zine.

♪ ♪ - To make a zine, all you need to do is write or draw something, photocopy it, fold it, you staple it.

You make hundreds of copies, and you sell and trade them with all your friends.

The storytelling became very personal, raw, and visceral.

Diane DiMassa did "Hothead Paisan."

And it's one of the most amazing little self-published comics to come out.

"Hothead Paisan" is a homicidal lesbian terrorist.

And she's filled with rage.

[upbeat music] And she goes through life reacting to all the injustice that's around her.

♪ ♪ - She was this-- almost like a cavewoman unleashed.

She walked like this.

And her hair was like crazy and sticking out.

And she would get so angry at men that she would grab like a labrys or something and chop them up or threaten to.

- We'd get away with a lot of stuff, because no one even knows to stop it sometimes.

They're not paying attention to us.

There's a lot of freedom there.

- Right now, the emphasis I'm seeing a lot more in the zine communities is about heritage, about culture, really more and more artists who are going back to their histories, back to their family history and saying, "This is who I am.

"This is what defines me, my identity.

"Yes, I'm a queer person.

But I'm also this other person."

[light music] ♪ ♪ - So then when the internet really became part of everybody's world, people started putting their comics online and getting responses.

And webcomics became a huge community for all cartoonists, particularly for people who were marginalized.

[light guitar music] ♪ ♪ [bat cracks] ♪ ♪ - I was in Mississippi for my grandmother's funeral.

And the very next day, I was on a two-lane highway.

I encountered a car veering into my lane.

And I turned my steering wheel sharply and went into a ditch.

It was a freak accident in that there was no damage to the car, no damage to me except my hands could feel my legs.

But my legs didn't feel my hand.

Scott had to fly to the hospital in Memphis.

And there was my mother and father.

And Scott came into the room and basically turned to the nurse and said, "I'm his partner.

"I'll need a cot.

I'll be sleeping next to him."

It wasn't any of this, "I'm wondering "if it's possible that I might be able to get a cot.

"I'm not sure.

I'm not really related, but he's my partner."

It was just gung ho.

My father is like, what the hell?

My mom is like, really?

She didn't have to be the primary person.

She got to see my partner do what partners do.

And boy, was that the beginning of an incredible relationship between Scott and my mom.

[indistinct chatter] [accordion music] I saw a few of John Callahan's drawings and work before I even realized he's a paraplegic.

♪ ♪ I ran into him, and he was in a chair.

And that was long before my accident.

♪ ♪ In no way was he gay, but he knew of my work in "Just Out."

So we connected as these two cartoonists.

Years later, I run into Callahan.

He goes, "What's up with you?"

"Well, there needs to be more than one paraplegic cartoonist in Portland."

It was a little bit of serendipity that I knew him, because there's this anger about the way you're treated and how it affects you that makes it fascinating for me to see how you represent that in your work.

♪ ♪ - So this is a cartoon that I was doing at that difficult period when I didn't know if I was going to be able to keep affording-- being able to afford being a cartoonist.

[telephone ringing] I was losing newspapers, losing bookstores.

My publisher said, "You know, the only sector "of this industry that's growing is graphic novels.

You should write a graphic novel."

And I thought, well, I've always wanted to tell this story about my family.

[accordion music] ♪ ♪ After graduating from college, I was going through all these old family photos.

And in an envelope of pictures of me and my brother at the beach, there was also a picture of this young man in his tighty-whities lying on a bed.

I had stumbled along in my blithe, happy way, coming out to my parents.

I unearthed their dark, hidden, painful secret... That my father had had affairs with other men and boys, some of his high school students over the course of their marriage.

And then, it was very shortly after that that my father died.

♪ ♪ My mom said, you know, I think he did it on purpose.

[tires screech] You know, it's hard to pinpoint the exact causal relationship between everything.

But yeah, I feel like if I hadn't-- if I hadn't come out or if I hadn't told them, things would have happened differently.

You know, he might still be alive.

I don't know.

Writing "Fun Home" was-- it was hard.

And I felt a little crazy.

I didn't know what I was doing.

I didn't know how to write a serious story like that.

I had Howard's "Stuck Rubber Baby" as a model.

But I knew that that had taken him years and years and driven him almost mad.

I spent many, many hours trying to recreate that blurry color photo.

And then I had to draw, you know, stuff like my father in the casket.

I posed for my dead father in the coffin.

I posed for almost everything in that book.

I mean, at the time, it was just a drawing aid.

But it was also a way for me to enter into the emotional world of the story.

♪ ♪ - I fell in love with the book.

I was immediately taken by the mere accomplishment.

Then when the story unfolded, it was like I know this person.

I always wondered about her background.

Not only is it explaining things; it's just-- I'm awestruck with every revelation.

♪ ♪ [telephone rings] - I wasn't thinking about it reaching a mainstream audience.

I didn't know who was going to read this weird book.

You know, I hoped that the people who read my comic strip would be interested.

But even that I wasn't sure of because it was so different and weird.

And it was becoming this much more literary-sounding thing that I thought they might not like.

And then it was actually successful.

Book critics read it and reviewed it as a book and not as a comic book, you know.

So that was a huge gift and a part of what enabled it to reach a bigger audience.

♪ ♪ Because of how comics had been progressing toward being taken seriously as a literary form in recent years, "Fun Home" made it over that threshold.

♪ ♪ - "TIME" magazine voted it one of the Books of the Year.

And I thought Alison has really reached the pinnacle.

And then the next thing I hear are these stirrings of a musical.

♪ ♪ - It is so strange to me.

I don't even know how to think about it.

Like the butch delivery woman I saw once with my dad in a luncheonette, how bizarre to see that very private and what I always thought was a super idiosyncratic memory, to see it turned into this scene in a Broadway musical.

I mean, I can't even believe I'm saying those words.

- ♪ Wearing your short hair and your dungarees ♪ ♪ And your lace-up boots and your keys ♪ ♪ Oh your ring of keys ♪ ♪ I know you ♪ - It was revolutionary that the play allowed this child to have this moment of recognition that she's a lesbian and also of desire, you know?

♪ ♪ - Me and Scott saw it with Alison.

Then it was nominated for Tony Awards.

And then she wins.

♪ ♪ - It was crazy.

It changed everything.

And it meant I got to keep being a cartoonist.

♪ ♪ I'm not even sure whose life I'm leading anymore.

♪ ♪ - I had met Alison a number of years before my accident.

Once the surgery was done, I was in a back brace.

I was longing to get back to Portland.

Maybe a day or two after I'd gone to work, I got a package in the mail.

And I opened up the box, and there was a little card saying, "I heard about your accident.

"And I wanted to send you a get well card.

"But then I knew other people might want to be "involved in it.

Love, Alison."

I thought, this is from Alison Bechdel.

I remember opening the box and seeing the very first panel and then pulling it and just watching the whole stream just unfurl.

And it just really, really touched my heart.

Because I kept recognizing the style of cartoonists that I really appreciated and admired and remember coming across the original drawing by Alison, and actually, one of my favorite characters of hers, of course.

I love the whimsy of the Trina Robbins panel and Jennifer Camper.

I love the contrast of hers, how dark they were.

- You're going to have to figure out the magic of it all.

Here we go.

Do you like that height?

Is that horrible?

A lesser man would need a hammer.

- I fancied myself as someone who really appreciated the communities that I was a part of.

This was the first time I so immediately felt embraced by the cartoonist community.

There's just something about being in that community where you genuinely don't feel like there's competition.

All of the ways that we represent the community and all of the ways our work--it's personal.

It's yet one more thing that I never want to take for granted.

♪ ♪ - We're no longer token sidekicks.

Were no longer sad stories.

♪ ♪ - I got my mainstream work because of the queer comics.

I'm very proud to have my queer roots and my mainstream roots.

But now, I can mix them together.

- A lot of the people coming to buy comics are actually parents.

And they're looking for material for their trans kid who just came out.

That's something that I definitely did not see when I started making comics.

[delicate piano music] ♪ ♪ [razor buzzing] - Queer comics have really created a space for complexity that didn't exist in a lot of other comics.

The space for different ways of being a person of color, different ways of being gendered.

It was really amazing.

It was like nothing I'd ever seen before.

♪ ♪ - Up next on "Independent Lens," a community of LGBTQ retirees celebrate life, love, and legacies of resistance in the short film, "Senior Prom."

[spacey music] ♪ ♪ - I did not, because I've been gay from day one.

- Yes, I did.

- I didn't.

I was too gay.

- And I was still doing straight.

[laughter] - Yeah, I double-dated with my best friend at the time, Gary, and I would have rather gone with Gary.

- Anne has made a difficult decision to go to her senior prom, a big night for most kids, but a night most gay teens avoid.

- The junior prom, semi-formal, is the best dance of the year.

The rules are simple, and they are very important.

- Wouldn't you rather go to the prom with your girlfriend?

- Oh, yeah.

But it wouldn't be allowed.

♪ ♪ - Oh!

66.

- Bingo.

- Bingo.

- Andi.

Okay, let's go check out Andi.

Andi, are you a top or a bottom?

- I have it on top.

- You're a top, okay.

- My name is Andi Segal.

And I'm 71 years old.

I became gay when I was-- gay, lesbian when I was 17.

I live in Hollywood in a gay and lesbian village.

Every year we have the prom.

You dress up.

You look your best.

Who can ask for more?

Many of us that are lesbian and gay or transgender, they couldn't go to their prom, because people are very cruel in the straight world.

- My name is Nancy Valverdi, born in March 1932.

I didn't go to anybody's prom because of my attire.

And I wasn't gonna put on a dress to please anybody.

♪ ♪ - Did you go to your high school prom?

- I went, but I wasn't very happy about it.

This was a heterosexual world.

This is a world where we can be ourselves.

- Welcome to prom.

[Earth, Wind & Fire's "Boogie Wonderland"] ♪ ♪ - ♪ Dance ♪ - I love to dance, and she loves to dance.

- Yes.

- Oh.

- Oh, you got lipstick on your lip.

- It's good exercise.

It's a sexual release as well.

- Oh, my.

Oh, my.

- Yes.

♪ ♪ - At 88 years old, I like to sit around and see other people dance and see the action.

By the law of average, I should not be here today.

I grew up in east Los Angeles.

I was the only Latin lesbian out there.

My friends, you couldn't tell they were lesbians, because they didn't dress like me.

I just like to wear my male attire.

I was about 17 first time they arrested me.

It was illegal to wear men's clothing.

I went to jail for that.

It was worth every bit of everything I went through.

Because now you can wear anything you want.

- ♪ Oh-oh-ahh-ahh ♪ ♪ Dance ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Boogie wonderland ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Dance ♪ - I remember the first dance I ever had with a girl.

She leaped on me, and she stuck her tongue in my mouth, okay?

And I liked it.

I liked it.

I didn't go to straight places after that.

But it was very, very hard for us to dance out in the open.

- Gay people want to be themselves, flirt, hold hands, kiss, just as heterosexuals do.

- Well, we weren't wanted in the world.

We were scorned.

We were outsiders.

We were outcasts.

I realized I was gay, but I'd already decided I wanted to be a priest.

I felt that I had to hide myself.

I was in the closet until I broke free.

And when you break that free there's no going back.

I came out as a gay man who was going to be a priest.

- We preach in our church that the people should be proud of themselves, proud of being gay, and all parts of their life, and being gay is good, so one should be proud of it.

[crowd chanting indistinctly] - Everyone should know that they are worthy of love, that they have worth in just being a human being.

[gentle music] - Raise your hand if you believe in love.

Do you believe in love?

Well, come on, seniors.

I have something to say about it.

♪ ♪ - I didn't feel that I deserved to be loved.

When my mom discovered that I was lesbian, she would say, "You're gonna grow up to be a nothing."

When I started going to the lesbian bars, that's where I found myself.

I was just dating, you know, different women, and then I met Skid.

♪ ♪ My life began with her.

♪ ♪ I never had anybody love me the way she did.

And I loved her because of it.

♪ ♪ She died in 2005, February 2nd.

When she passed away, she's gone.

She's not in my bed holding me and telling me that she loves me.

I know that I'm blessed to have her for 36 years.

You know what?

I--all those years that I had her.

♪ ♪ It was time for me to move on.

I went to grief group at the village, and Nancy was there.

I looked at her, and I thought, "My God, she's gorgeous."

♪ ♪ They need to know, the young ones, that you can have lasting relationships until the end, that you can make it last.

♪ ♪ - Now we're at the big moment of the evening where we're gonna crown a king and queen of the senior prom.

[cheers and applause] We're first gonna do the oldest.

Who here is between the ages of 80 and 85?

Raise your hand.

- I look in the mirror, and I see this older man.

Try and remember when you were 21, 22, 23.

That's the person that's inside my skull.

- Gertie and Robert are our new king and queen.

Come on up.

[cheers and applause] - We've come quite a nice distance.

But there's still more to go.

[cheers and applause] We're here, we're queer, and we're not going to curl up and die.

["Dancing Queen" playing] ♪ ♪ - Are you all having fun tonight?

[cheers] - Good night, everybody.

- Like a queen.

- Thank you.

Good night.

I look forward to seeing the whole bunch of you at the next big affair.

Ciao, bambinos.

♪♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S24 Ep6 | 30s | Five queer comic book artists journey from the underground comix scene to the mainstream. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Indie Films

Meet a brotherhood of Marines struggling to overcome trauma from their deployment to Afghanistan.

Support for PBS provided by: